Religion and Truth: Reflections on Heretic

Why Religion Once Had Such Power Over Us, And What This Tells Us About The Nature Of Truth

Two fish were swimming.

The first fish turned to the second and said, "The water's lovely today!"

The second fish looked confused. "What's water?"

"The thing we invented so we’d have something to swim in!" replied the first.

I watched the movie Heretic in the cinema this weekend, and it set the thought-wheels in motion for this post. I want to explore why religion had such a prominent role in our past, and what that tells us about the nature of truth.

[Spoiler alert: themes from the film are explored below]

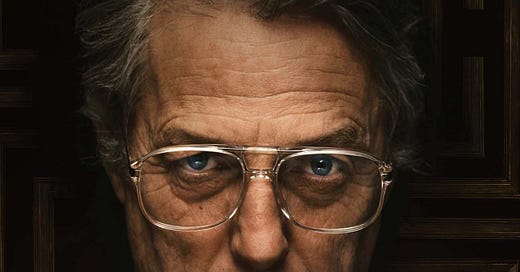

In Heretic, Hugh Grants character, Mr Reed, uses unconventional methods to encourage his door-to-door Mormon guests to question their belief in the face of the glaring problems and inconsistencies faced by their religion.

Reed concludes that the one commonality between all religions is they’re effective mechanism to control what people think and do. Perhaps those in charge really believe in what they propagate, but the effect is always control over people.

This head-on adressal of religious inconsistency is a thought provoking and brave line of reasoning from the film’s producers, and reflecting on the film and its message can give us some insight about what truth is to us.

One theme Reed prods at but leaves relatively unexplored is why we allow(ed) religion to have such a hold over us. Childhood indoctrination is touted, sure, but why did the chain of childhood indoctrination start in the first place? What was it about religion that drew us all in so irresistibly?

My take on this, which I’ll build out for the rest of this article, is that ideas are considered true as long as they’re useful in answering important questions about the world. Given this, pre-science, religion was a useful source of answers in a world we really didn’t understand. In fact, religion could answer both ‘physical’ questions – like how the universe came to be, or the origins of mankind – and ‘social’ questions like the difference between right and wrong and how we ought to treat one another.

Religions unique selling point was the stunning breadth of questions it could answer in a very confusing world. But this was also its downfall. As the scientific revolution progressed, doubt over religions answers to the ‘physical’ questions grew unignorable, undermining the whole thing. Slowly but surely, religious ideas diminished as science proved more useful in answering questions about the world.

“Ideas are considered true as long as they’re useful in answering important questions about the world”

As society lost its faith, contemporary thinkers worried that we’d descend into immorality and anarchy. But this didn’t happen. That’s because ideas about how we should live amongst each other – the social truths which had traditionally been the domain of religion – remained useful, so survived. People still believed in the importance of treating others with respect and fairness as they did before, because everyone always understood a society can’t function without these rules of conduct. Religion didn’t create and uphold these values; rather the values predated the religions, which acted as a container for them.

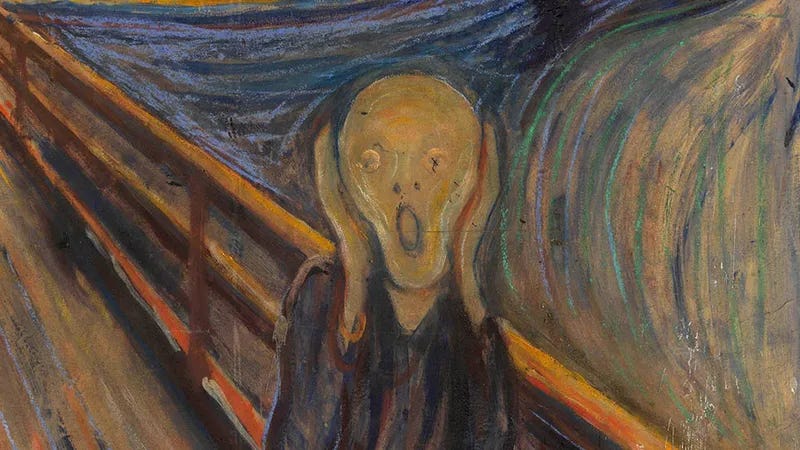

Edvard Munch’s The Scream. Feeling alone in the universe can be terrifying.

I think this is an important truth [true in so far as it helps explain experience!] about our relationship with truth; we consider something true if it’s useful. To make this clearer, consider something uncontroversially true: it’s wrong to kill innocent people for no reason. No God, angel or anything else told us this – we created the rule for ourselves, and I’d hypothesise it’s been accepted in every human society that’s ever existed. Why is it so popular? Because its universally useful. So long as we live in groups, we need this rule. No society can function unless this rule is accepted as true.

“Religion didn’t create and uphold our social values; rather the values predated the religion, which acted as a container for them.”

While it’s easy to look back on the religious past and view their truths (and the people that believed them) as stupid, when we see truth as usefulness that condescending view of the past no longer holds water. Their truths were exactly the same as ours; the most useful available, given the facts known.

By extension, what we consider true will change as we progress into the future. As scientific apparatus improves we’ll develop richer theories of the laws governing the universe, our truths will become more refined and our current beliefs will become redundant. Accepted scientific theories of today which are so useful in explaining the patterns we see in the world - theories such as evolution, the Big Bang, atomic structures etc. - will all improve.

Here I need to raise an important dimension I haven’t yet discussed. Something is true so long as they’re useful; but useful to who? Me? You? The UK? Humanity?

My rosy outlook for the continual development of physical truths is based on the fact that scientific discovery is basically useful to everyone (with some major atomic exceptions…). The discoverer becomes rich and famous, our theories of the world become better which enables us to invent new and brilliant technologies to improve everyone’s lives. This means all parties want to foster its development.

The social truth realm is different. Bar the simple basic truths, what’s useful to me might in fact be very un-useful to you. That every Substack blogger receives a free car with each post would be a very useful rule for me, but not so for those who have to pay for my car. In this way, there will always be tension between competing groups over social truths.

Another difference which means physical truths improve more reliably is that the subject matter of physical truths – the laws of the universe – are constant and unchanging, facilitating learning and progress. Social truths are different, with the constituency of societal groups and the challenges facing them constantly evolving. This makes social truths much more prone to upheaval, preventing the type of compounding progress seen in physical sciences.

To sum up, in this post I’ve laid out my thinking on how what we think of as ‘true’ depends only on the usefulness of the statement in answering important and practical questions we have about the world. This aligns my worldview with Pragmatism. I find this philosophy attractive because it can explain why what’s ‘true’ changes over time. I’m optimistic about our ability to improve our physical truths – those in the domain of science over time, but I don’t think social truths will ever improve in the same manner because these are a different type of truth.

Anyway; I’d recommend watching Heretic if you haven’t seen it (there’s a lot I haven’t spoiled in this post!).